2012 – Highlights of the Increasing Intersections Between Science and Law

- Kirk Hartley

- Dec 31, 2012

- 4 min read

(Image courtesy of Nature)

_______________________________________________________________________________

As 2012 exits, here’s a brief look back at a few of the many ways the year highlighted some of the rapidly increasing intersections between law and science.

Superstorm Sandy provides an easy, concrete example. Indeed, the name itself reveals increasing attention to science – technically, it was not a hurricane when it landed, but the harm was immense.

At the small picture level, Sandy opened the door for years of argument between insurers and insureds about insurance policy terms, damages and causation at the building by building level. And, some who went through Katrina marvel at the difference that may lie in the scientific specifics.

The big picture issues from Sandy tie to global warming and its role in the storm and the immense harms. Global climate treaty issues, for example, will arise in 2103 at Doha and EPA will keep regulating, or trying to regulate. Meanwhile, one might think about Sandy’s lesson for paying attention today to current scientific thinking and predictions. For example, one can look back at the global warmingpredictions of years ago. Salon, for example, highlights the following:

"In 1988, NASA scientist James Hansen, sometimes called the godfather of global warming science, ran computer models that predicted the decade of the 2010s would see many more 95-degree or hotter days and much fewer subfreezing days. This year made Hansen’s predictions seemed like underestimates. For example, he predicted that in the 2010s Memphis would have on average 26 days of more than 95 degrees. This year there were 47."

Science and law also intersected at the U.S. Supreme Court. In its Prometheus opinion, an often-fractured Supreme Court united 9-0 to knock out a patent claimed for a method of treating disease by finding and measuring levels of a drug after administration. Patents cannot cover the laws of nature, the Court held:

“Phenomena of nature, though just discovered, mental processes, and abstract intellectual concepts are not patentable, as they are the basic tools of scientific and technological work.” Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U. S. 63, 67 (1972). And monopolization of those tools through the grant of a patent might tend to impede innovation more than it would tend to promote it.

***

[As to arguments about the breadth of patentability], [w]e do not find this kind of difference of opinion surprising. Patent protection is, after all, a two-edged sword. On the one hand, the promise of exclusive rights provides monetary incentives that lead to creation, invention, and discovery. On the other hand, that very exclusivity can impede the flow of information that might permit, indeed spur, invention, by, for example, raising the price of using the patented ideas once created, requiring potential users to conduct costly and time-consuming searches of existing patents and pending patent applications, and requiring the negotiation of complex licensing arrangements. At the same time, patent law’s general rules must govern inventive activity in many different fields of human endeavor, with the result that the practical effects of rules that reflect a general effort to balance these considerations may differ from one field to another. Hovenkamp, Creation without Restraint, at 98–100."

For 2013, the Court will hear the Myriad Genetics "gene patent" case brought by the ACLU and other advocacy groups to challenge patents on identification of genes and other items created from genes. The case arose from a challenge to the patent claim for the BRACA 1 and 2 genes that causes so much breast cancer – a timeline is here. There, at the District Court level, Judge Sweet cogently laid out the reasons that block patents on genes. And the Supreme Court’s Prometheus opinion rather emphatically rejected "patent think," a point of great frustration for some patent lawyers for some members of pharma. The same lawyers are trying to figure out ways to limit the impending loss.

2012 also included scientific findings that will be part of future waves of cancer litigation arising from increasing and massive numbers of cancers , and increasing numbers of substances deemed carcinogens. For example, consider tobacco. This year bought news of scientific evidence of nicotine causing multi-generational harms (that is, mom’s smoking does harm the fetus) and an epigenetic fingerprint for cellular changes caused by tobacco smoke.

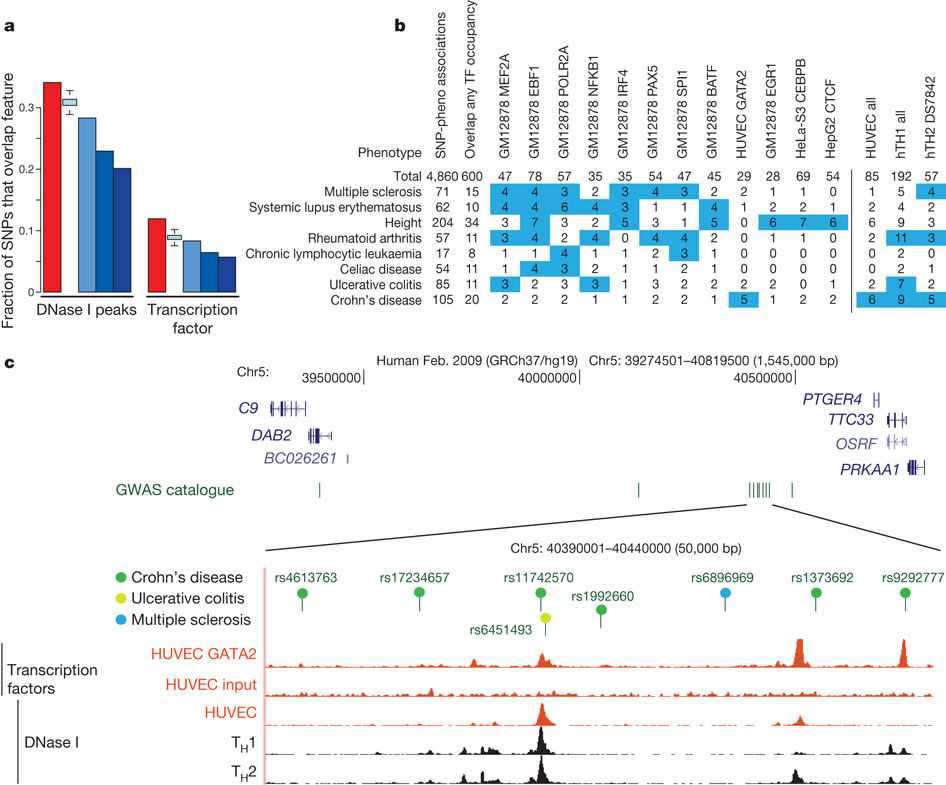

More fundamental facts also were found that will play into future litigation involving cancers and other diseases. Specifically, the National Institute of Health went public with massive amounts of data from the decade long Encode Project, which followed up on the Human Genome Project (HGP). The Encode project produced genetic maps for millions of bits of genetic changes not covered in detail in the HGP. Indeed, we used to assign the label "junk DNA" to some unknown regions of DNA The junk became not junk when dozens of papers were released simultaneously, all with complete open access data free to all scientific users. Nature published much of the data – and easy to follow explanations. Thus, molecular biology continued to explode with exponentially massive growth of data and knowledge. The chart at the top of this page highlights some of the findings, including scientists closing on on causes for Crohn’s disease.

As the knowledge revolution continues in molecular biology, causes of diseases will become clearer, and lawyers and other professionals will encounter well more than just "the next asbestos." Meanwhile, supercomputers and research "in silico" will soon create even more to know, and litigate. One hopes that more of tomorrow’s lawyers are today studying biology and bioinformatics, and are preparing to work in multi-disciplinary teams and business structures. Note also that scientists are racing ahead, regardless of whether lawyers are ready.

Best wishes to all for 2013. It seems safe to predict an interesting year is about to arrive.

Comments